Why Congress Controls D.C.: An Explainer on the District’s Unique Status and the Fight for Statehood

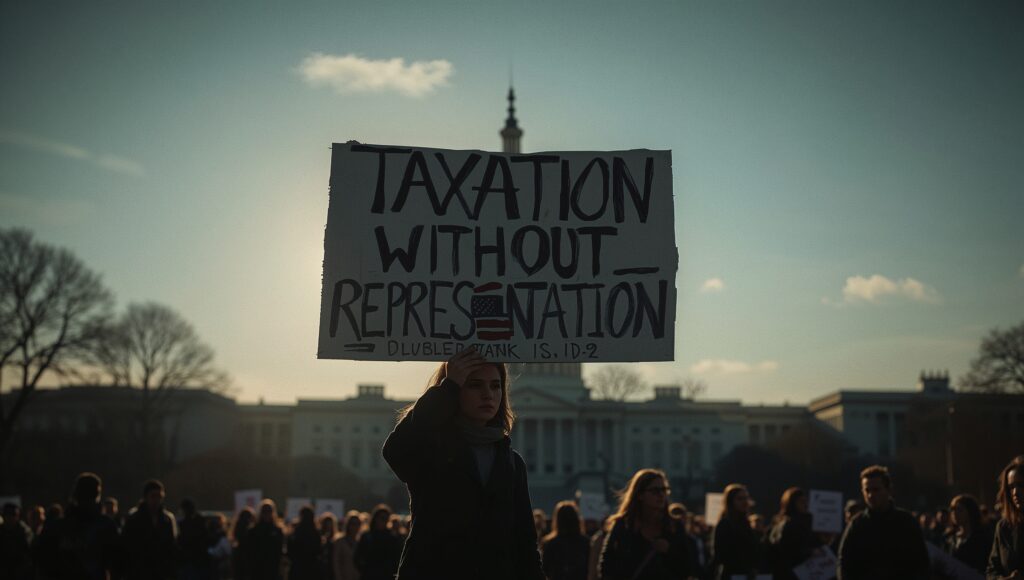

The debate over D.C. statehood centers on the democratic rights of its residents, who pay federal taxes but lack voting representation in Congress.

More than 700,000 American citizens live in Washington, D.C., a population larger than that of two U.S. states. They pay more in federal taxes per capita than residents of any state, yet they lack a voting representative in the House and have no senators to represent them in Congress. Their local laws can be overturned by federal politicians, and their local judges are appointed by the President.

This unique and contentious situation stems from a single clause in the U.S. Constitution that has shaped the District of Columbia for over 200 years, creating a continuous tension between the need for a federal capital and the democratic principle of self-governance. Here is an explainer on why Congress controls D.C. and the deeply polarized debate over its future.

Why Is D.C. Not a State?

The unique status of Washington, D.C. is rooted in the U.S. Constitution. Article I, Section 8, Clause 17—known as the District Clause—grants Congress the power to “exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever” over a federal district that would serve as the seat of government.

The Founders’ reasoning was strategic: they wanted to ensure the national capital would be independent from the influence of any single state. This concern was highlighted by the Philadelphia Mutiny of 1783, where the Continental Congress was forced to flee the city because the state government failed to protect them from angry, unpaid soldiers. As James Madison wrote in Federalist No. 43, the capital needed complete authority for its “own maintenance and security.”

Established by the Residence Act of 1790 on land ceded by Maryland and Virginia, the district’s creation had a “momentous consequence” for its residents. The Organic Act of 1801 formally placed D.C. under congressional jurisdiction, and in doing so, stripped the citizens living there of their right to vote in federal elections as they previously had as residents of Maryland and Virginia. This act created the grievance of “taxation without representation” that defines the statehood debate today.

What Is “Home Rule”?

For much of its history, D.C. was governed directly by presidentially appointed commissioners. It was not until the

Home Rule Act of 1973 that the city was granted an elected Mayor and a 13-member City Council. The primary goal of the act was to “relieve Congress of the burden of legislating upon essentially local District matters”.

However, Home Rule is not autonomy. The act is a delegation of power, not a permanent transfer. Congress explicitly reserved “the right, at any time, to exercise its constitutional authority as legislature for the District,” establishing that D.C.’s self-governance is a privilege that can be revoked, not a constitutional right.

How Does the Federal Government Still Control D.C.?

Despite having an elected local government, Washington, D.C. remains subject to extensive and active federal oversight mechanisms that do not apply to any state.

- Congressional Review of Laws: Every law passed by the D.C. Council must be sent to Congress for a “layover” period of 30 to 60 days. During this time, Congress can pass a joint resolution to block the law from taking effect, effectively vetoing the will of D.C.’s elected officials and residents.

- Budgetary Control: While D.C. raises its own revenue through local taxes, Congress retains ultimate authority over its budget. It frequently uses this power to attach policy “riders” to federal spending bills, which prohibit D.C. from using its own money for specific purposes that are politically unpopular at the national level, such as funding for abortion services or legalizing recreational cannabis sales.

- Control Over Courts: All judges on D.C.’s local Superior Court and Court of Appeals are nominated by the U.S. President and must be confirmed by the U.S. Senate. This divorces the local judiciary from local accountability and can lead to long delays in filling judicial vacancies.

- Control Over Security: Unlike in every state where the governor commands the local National Guard, the D.C. National Guard is commanded by the President. The President also has the authority to federalize the city’s Metropolitan Police Department at any time.

The Heart of the Matter: “Taxation Without Representation”

The central democratic issue for D.C. is its lack of a voting voice in the very body that governs it. D.C. residents have

zero senators and only a non-voting Delegate in the House of Representatives, who can draft bills and vote in committee but cannot vote on the final passage of legislation.

This lack of representation exists despite the fact that D.C. residents pay more in federal taxes per capita than any state in the union. The slogan “Taxation Without Representation,” famously printed on the city’s license plates, is a direct echo of the American colonists’ core grievance against the British crown. This “power vacuum” leaves the city vulnerable to federal interference, as politicians from other states can impose their will on D.C. residents with no political accountability to them.

The Polarized Debate Over D.C. Statehood

The most prominent proposed solution to this democratic deficit is to grant D.C. statehood, a goal embodied in the “Washington, Douglass Commonwealth” bill (H.R. 51). The debate is sharply polarized along party lines.

Arguments for Statehood: Proponents argue that statehood is a fundamental issue of civil and democratic rights. They contend it is the only way to grant full voting rights to over 700,000 U.S. citizens and end “taxation without representation.” Advocates also frame it as a crucial racial justice issue, as D.C.’s population is nearly 45% Black, and they argue that opposition is partly rooted in a desire to disenfranchise a diverse, majority-minority electorate.

Arguments Against Statehood: Opponents raise constitutional objections, arguing that the Founders intended for a neutral federal district and that statehood would violate this principle. Some also point to complications with the 23rd Amendment, which grants D.C. three electoral votes for president, arguing it would need to be repealed.

However, the most powerful opposition is political. D.C. is a reliably Democratic-voting jurisdiction, and statehood would almost certainly result in the election of two new Democratic senators and one Democratic representative, shifting the partisan balance of power in Congress. This has led many Republicans to label the effort a “partisan power grab.”

While the statehood bill has passed the House of Representatives twice in recent years, it has stalled in the Senate, where it faces unified Republican opposition.